My Star Trek Episode at Everest

As we approach the 50th anniversary of Star Trek, I thought I’d write about how many experiences in my life have intersected with- and have been affected by its legacy. In late April 2009 I found myself at Everest Base Camp for a month. I was living at 17,600 feet in Nepal 2 miles from China and 2 miles from the highest point on our planet. I was surrounded by the epic majesty of the Himalayas, a thousand people supporting several hundred Type A individuals with a shared intent to summit the mountain and stand in the jet stream. And all of this was enabled by the austere and noble Sherpa people. I was on a mission not unlike a space mission. My team mate was my long-time friend Scott Parazynski, an astronaut. And I had 4 small Apollo 11 Moon rocks in my pocket. Meanwhile, another friend, John Grunsfeld, was in orbit flying over us as he and his crew fixed the Hubble Space Telescope.

I could just stop there and what is in these sentences would be cool enough. This had all the makings of a Star Trek episode – and I knew it.

Trekking Up To Everest

It took a lot of effort for all of us to get here – 10 days of nonstop hiking with constant physiological adaptation to an extreme environment. Everyone gets sick – in one way or another eventually. If someone had just beamed in to Everest Base Camp they’d have fallen over due to lack of acclimatization. That’s why you take your time trekking in so as to adapt. Yea, I did a “trek” to get there. Similarly if you beamed from Base Camp to the summit you’d fall over instantly. Hence the need for Everest climbers to acclimatize even further.

My job was to stay at Everest Base Camp (analogous to working aboard the space station/space shuttle – or an Apollo Command Module in lunar orbit) and relay news of Scott’s climb (his EVA, if you will) while he ventured forth into the so-called “death zone” on Everest. His goal: being able to see an orbital sunrise – on Earth. Back home our mission support was provided by seasoned CNN journalist and almost-astronaut Miles O’Brien. Meanwhile another friend, astronaut John Grunsfeld (also a mountaineer) would spend several weeks in orbit fixing Hubble while Scott and I were at Everest.

Scott, Miles and I were doing this project for a variety of reasons – working backwards from ‘why the hell not’. Miles was supposed to have joined us in 2009 but a production commitment nixed that idea. So Miles became our global news anchor in New York City attracting media attention to our efforts and filing updates from his laundry room. In the mix was an effort to help bring visibility to the Challenger Center for Space Science Education – we were all members of the board of directors. I actually voted to put Scott on the board of Challenger Center while in Nepal sitting in a dirt-floored Internet Cafe in Dingboche, Nepal while staying at the “Hotel Arizona”. It was neither, BTW.

The 4 little Apollo 11 Moon rocks that I took to Nepal

In my chest pocket 24/7 was a small lucite pellet shaped like a gumdrop embedded with 4 small moon rocks picked up by Neil Armstrong during Apollo 11. Those moon rocks went to the summit with Scott and, a year later, were flown to the ISS (video) on STS-130 along with a piece of the summit of Mt. Everest. These rocks are mounted inside the cupola with an ever-present view of planet Earth rolling by below. Bob Jacobs from NASA Public Affairs had worked diligently with me to get the rocks loaned to Scott and I for this trip.

Part of the review process for loaning out moon rocks involves a committee of scientists. During that time one of the committee members was planetary scientist Meenakshi Wadhwa. She later met Scott as a direct result of this moon rock loan and were later married. But that’s another story. There is something magical about moon rocks.

Apollo 11 moon rocks on the floor of my work tent surrounded by similarly sized flecks of Mt. Everest

I had given a lot of thought to how I’d do PR at Everest. This was so cool. The options were almost limitless. We had an astronaut, a moon rock, the highest mountain on Earth, a CNN news anchor, and all manner of exotic locales, ever-present risk, and once-in-a-life-time experiences.

Scott had almost made it to the summit in 2008 – but a back injury forced him to call off his attempt. I was supposed to be there on that trip I was packed and ready to go. But my participation evaporated before it even started when China’s Olympics-oriented heavy-handed censorship of activities in the Everest region made it highly probable that I could be arrested and/or deported for being “media”. So I did what I could from my home in Virginia. My wife chuckled every night when I got a call around 11 pm ET with no caller ID i.e. via Iridium. “Scott’s calling” she’d say.

I spent more than a year preparing for my time at Everest Base Camp. But I had neglected to fully consider what would happen on the trip there. Little did I know that an Iridium phone call to my wife and a little lucite gumdrop with tiny moon rocks inside would provide me with some of my most profound experiences in Nepal – before I even reached Everest.

Away Team Encounters In The Khumbu

One night in April 2009, as I trekked through the Khumbu region toward Everest, I stayed in Dingboche (elevation 14,470 feet) at the aforementioned Hotel Arizona. I went outside to call my wife on the Iridium satphone. It was impossibly dark with a sky full of stars unlike any I had ever seen. I was just mesmerized. It was so dark that I literally walked right into a small yak that was wandering around the Hotel Arizona.

At one point my trekking guide Tashi came out. Tashi is a Sherpa who has reached the summit of Everest 12 times. He asked me why I was looking up at the sky. He had seen satellite phones before, so he knew what they did. I explained to him that it was hard to get a signal for more than a few minutes due to the high peaks surrounding us. So, I waited to see if I could spot an Iridium satellite (easy to do) and then dialed my wife. I knew I’d lose the call as soon as the satellite passed behind a mountain – but having the satellite in sight allowed me to parse my conversation.

Keith and Tashi at Everest Base Camp

Tashi is a very smart guy. But he was a bit perplexed about my satellite spotting. So I taught him how to do it and explained the different types of satellites and their orbits. Like his neighbors, Tashi had always assumed that all of the moving lights in the night sky were airplanes. When I told him that they were satellites lit by sunlight he asked how they could be lit by the sun at night. I asked him why some mountain peaks were still visible well after the sun goes down or glow before the sun rises. He answered matter of factly that this was because the mountains were very high. I then asked him to imagine a mountain 100 km tall – where satellites are – and said that this is why they were still visible. Having had the experience of 12 Everest summits under his belt and gazing out over vast expanses, Tashi immediately got the concept. Several days later I saw him teaching and explaining my satellite hunting tricks to several other Sherpas.

To this day I get a shiver from this – it was a very Star Trek moment – teaching someone what the “lights in the sky” were – with a piece of the Moon in my pocket on my way to meet a space traveller. Tashi was very psyched about that. But this was not my only Star Trek moment in Nepal.

Several days before, as we worked our way north from Tengboche through the Khumbu, Tashi and I stopped in his home village of Pangboche. He and his wife run a teahouse and lodge there. On our way out of town I asked Tashi if we could stop at the local monastery and get something blessed. All climbers stop at this temple or another to get themselves and their climbing gear blessed. I then explained that I had moon rocks in my pocket. I had mentioned this to Tashi before (but to no one else) but I expected that Tashi thought that I was another rich crazy westerner. So I explained things in greater detail and showed it to him. He held it very reverently and then handed it back to me. We stopped at the temple a few minutes later.

Tashi had studied to be a monk for many years so he was a skilled adept who explained many things to me. This temple – like many others – had stood in this spot for centuries in one incarnation or another. There was a rock inside where some of the flying monks in this valley once touched down. This is also the place where the Pangboche Hand (supposedly from a Yeti) resided for years until someone stole it.

Eventually the local monk (actually a part-time monk wearing a baseball cap) agreed to bless the moon rock. He seemed to be ho hum about it and was perplexed as to why I wanted this little piece of plastic to be blessed. But I had given him 10,000 rupees so, why not. I asked Tashi if he had explained what it was to the monk and he nodded that he had. I asked Tashi to do so again – and to so more thoroughly.

After a minute or so the monk’s facial expression changed dramatically. He slowly took the little piece of plastic and moon rocks and reverently touched it to his forehead. To buddhists this is the most scared part of one’s body and to do something like this implies immense respect for something.

Over the coming days I kept the rock in my pocket. Every now and then if we stopped to talk to local residents, our porters etc., I’d explain via Tashi what it was. Without exception they all held it and touched to their foreheads – or to their children’s. They were all exceptionally appreciative toward me for allowing them to hold these little moon rocks. To many buddhists – and many Nepalis – the moon is sacred. Indeed, it is one of the two symbols in Nepal’s flag. And I had allowed them to hold something that is truly sacred for a moment. That quickly sunk in. This moon rock was something special.

Moon rocks being blessed by a monk

Later when it became known that we had the moon rock I showed it to westerners. At most they said “that’s cool” or “its kinda small, isn’t it?” Some asked if they were real since that whole moon landing thing was faked. Typical western cynicism. Oddly, the Nepali Sherpas in the Solokhumbu region that I spoke with about space and the stars all knew than people had walked on the Moon. Yet none of them knew that there was a space station. I pointed it out once when it flew over and told several Sherpas that there people on board. That was news to them. As was the case with the satellite sightings I also get shivers when I recall these encounters with the moon rocks.

Think of all of those Star Trek episodes where people on some planet suddenly encounter something such as an artifact from another world for the first time or that ancient legends speak of things from the stars. To be honest, had I been given the chance, I’d have walked all over the Khumbu region letting every person hold the moon rocks. I really did feel like I was in a Star Trek episode before I ever reached Everest Base Camp.

A few weeks later Scott and I stuck our heads into the large tent where all of the Sherpa porters, cooks, and other personnel ate. I pulled out a heavy package and opened it. Inside was a thick stack of photo prints of an image Scott had taken of Everest from orbit during STS-66 way back in 1994. One of the camp managers explained to the Sherpas inside the tent what we were going to give out.

The photo of Everest that Scott took from orbit on STS-66 that we handed out to each and every Sherpa

As we handed the photos out more than one of the Sherpas bent their head forward so as to touch the photo to their forehead. Scott and I were both moved by this. It is an unfortunate reality that many of the Sherpas who work to support climbers are not treated with the respect that they warrant. And yet here was a space traveller making a point of seeking them out.

There was another resonance with my trip. This time it was between me and a statue. At one point in my trek up to Everest Base Camp I visited Khumjung. This village features a school built as the result of the multi-decade efforts of Sir Edmund Hillary and is often called the “Hillary School”. I managed to pose for a moon rock selfie with the statue of Sir Ed in the courtyard of the school. After his historic trip to the Moon, Neil Armstrong became close friends with Hillary. Few people could better understand what these guys had done than each another. They later traveled the world together – including a trip to the North Pole.

Soon, rocks picked up by Armstrong would go to the place that Hillary had first been with Tenzing Norgay and then rocks from both places would travel into space together. I sent a photo back to my friend Dan Bennett who was President of the Explorers Club (of which Scott and I are Fellows). Lets just say my Explorers Club comrades were really excited about the historic resonance of this photo for two of our organization’s most illustrious members.

Getting to Everest is not easy. Sure, you can pay to trek in for a day. But spending a long time at Base Camp requires money and support. Scott was one of the climbers featured in the third season of the Discovery Channel series “Everest to the Limit”. In addition, I was working as a blogger/videographer for Discovery Channel. We also had some strong financial support from SPOT, the satellite tracker device. We had hardware on loan from NASA Ames Research Center and moon rocks from NASA Johnson Space Center. We also had equipment on loan from Ocean Optics, a manufacturer of scientific imaging systems. We were also carrying an Explorers Club flag as an official flag expedition and were representing the Challenger Center for Space Science Education. Everyone who goes to Everest for a prolonged period has multiple backers and sponsors. We were no different.

Keith holding 4 little moon rocks in his hand at the statue to Sir Edmund Hillary in Khumjung, Nepal

In the Star Trek universe when you encounter a civilization less technologically advanced or unaware of space travel you are supposed to adopt a non-interference policy. Its called the Prime Directive. However Scott and I were doing exactly the opposite. Scott had more experience than I but yet we both still had the proverbial beginner’s mind when it came to dealing with the Sherpa people. Contrary to the Prime Directive from Star Trek, our version prompted us to constantly think of ways to enhance Nepal’s access to space. We continue to pursue this directive to this day.

Planning For The Summit

In 2008, within a few months of being back from his first try Scott and I were already talking of how to make a second attempt – and do so bigger and better. Doing education and public outreach from Everest was not exactly easy in 2009. The communications infrastructure at Everest was still essentially comprised of what you personally brought with you. In my case we had an Iridium phone and a BGAN satellite unit. And yes the phone bill was expensive.

From our friends at NASA Edge “Wow! Apparently, we have a small contingent of fans in Nepal! Or course, they are not there for NASA EDGE. These two Everest Insiders and Outsiders are at Mount Everest base camp preparing to make their epic ascent to the summit. You can follow their progress, along with their entire team. And even though they have their very own goofy co-host, we expect nothing but success. Stay safe guys! The NASA EDGE Goofy Co-Host”

Shortly after I arrived I placed a call from our BGAN to NASA JSC and then to the ISS. You simply dial a phone number and they make it happen. I have done it from my home office more than once to interview crew members in the ISS. The conversation between Scott, some visiting folks from JSC, and the ISS was pretty much “Weather is here, wish you were beautiful”. Several days earlier, just before I arrived, Mike Barratt got an Iridium call from Scott with three singing Sherpas wishing Barratt happy birthday. Unbeknownst to Scott and I, Mike Barratt also had another Apollo 11 Moon rock (albeit a bigger one) with him on the ISS, having been delivered by STS-119 only a few days before. These Moon rocks certainly manage to get around.

But I wanted to do more than fun phone calls to outer space. I wanted to do things that really resonated historically. Scott was about to become the first human to fly in space and stand atop the highest point on our planet. Phone calls from Base Camp were easy. Calling from the summit – that was going to be a challenge.

The Khumbu Icefall as seen outside my tent

It was not hard to find inspiration in this astonishing place. Every morning I’d wake up to a vista outside my tent as I opened the flaps: the Khumbu Icefall – a slow motion river of ice creeping down the side of Everest. If you are climbing from this side of the mountain then you need to go up through it. It is this icefall that let loose several immense avalanches in 2009. To minimize the dangers from constantly shifting house-sized blocks of ice, climbers try and go up as much of it as they can while it is still dark and the landscape is frozen together. More than once I’d wake up very early to peer out of my tent to see small points of light forming a snaking line up the icefall. As morning approached a blue hue became noticeable. At one point I recalled that scene from “Star Trek VI The Undiscovered Country” where Kirk and McCoy escape a prison and cross a vast ice field.

One of the things we’d hoped to do was get Scott to talk to Neil Armstrong from the summit. Despite NASA’s best efforts that never happened. I also had notions of getting a call from Scott to the White House. That never happened either. We also tried to work a way for Scott to talk to the crew of the ISS or with Space Shuttle Atlantis. Alas, the timing for phone calls to either ISS or Space Shuttle Atlantis were not in synch with what eventually became Scott’s early morning summit plan and established plans for both Atlantis and ISS.

Since everything at Everest was based on weather and timing – it was in constant motion with regards to the actual date of the summit push. It was simply not possible to make the call work. Also, Scott would have also had to use our Iridium satellite phone to dial to JSC and then hope that the connection did not die (it always did) and getting a signal was equally challenging. Oh yes – and then there’s the small keypad to use with fingers that would freeze. A Star Trek communicator or badge would have been nice to have.

The other option was for me to use my BGAN unit at base camp (much more reliable), dial into JSC, have JSC link up with people in space, and then I’d rotate the phone back and forth so that Scott and the crew would have a chat over the radio handset. Of course I’d have had to say something like “ISS this Everest Base Camp. How do you hear me?” and then do a hand over to Scott on the summit saying something like “Everest summit this is Everest Base Camp I have ISS on the phone”. THAT would have been beyond cool. Kinda like saying “Kirk to Enterprise” – for real. But Scott wanted to make as early a summit push as he could to avoid the morning commuter traffic and see the sun rise – and that aspect of his mission took precedent over all of my PR stuff. But we tried.

Scott talking to Miles O’Brien via a Mac labtop and a BGAN (behind the Mac)

Phone call problems being what they were, we had video and still cameras. The still camera Scott took with him is a cheap one I bought at Best Buy. There is a climber’s rule of sorts that if you bring an expensive camera on your climb and something puts it at risk you might be tempted to do something to save it and risk yourself. But if it is a cheap camera then you don’t because who cares. The cheap camera worked just fine. Scott also had a video camera with solid state memory (we did not want to risk using one with a hard drive). I had an identical video camera just in case Scott’s failed – and loaned him my wide angle lens. It also worked just fine.

Scott also had my Gigapan unit and took the highest Gigapan images ever taken at the time. But getting that thing to the summit – much less using it – was out of the question. And if all else failed the Discovery Channel (one of our sponsors) had a crew documenting Scott’s climb on “Everest To The Limit“. One way or another the moment would be captured.

Other than the obvious pictures people take on the summit, there were many memorials we wanted to document. Scott and I went over the things he’d do on the summit – this included the “summit bling” he had to carry. We photographed every item on the floor of my work tent. Scott actually had a database of things he was carrying including their weight. Every gram counted. You have to consider that he was going to be dead tired – literally cold and possibly disoriented. Getting down was more important than getting up.

Since the new Star Trek movie was in theaters back home I hit on the idea of having Scott give the Vulcan salute from the summit – he also sort of looks like actor Chris Pine – so that was a bonus. But that idea got rejected when we realized that in order for the Vulcan salute to be visible Scott would have to take his heavy mittens off and for the salute to be seen – and fingers can freeze pretty quickly 5 miles above the Earth. Scratch that idea.

We planned how Scott would hold up the moon rocks on the summit. We knew when the Moon would rise, where it would be in the sky etc. We planned to take practice pictures at Base Camp to figure out how to have Scott’s Sherpa Danuru frame the photos on the summit. Since the small lucite gumdrop was easily dropped we McGyvered a larger container out of two lids from the ubiquitous cans of Pringles in the mess tent and some duct tape. We had been using code words for the moon rocks since we really did not want to advertise the fact that we had moon rocks. The moon rocks were therefore called “The Nugget” and the container we built was called the “Nugget Containment Device” – since we were both such space nerds.

The Nugget inside the Nuggett Containment Device

That evening, after dinner, Scott and I went outside to do some practice shots for how he might get the Moon and our Moon rocks in the same picture on the summit. At one point I was playing around and we got the small piece of lucite with the rocks withing the Pringle can lids to eclipse the rising Moon. Eclipsing the Moon with pieces of the Moon – at Everest Base Camp with an astronaut. That’s yet another sentence that is a totally self-contained story in and of itself.

Eclipsing the Moon with pieces of the Moon

As I looked at the Moon rocks – eclipsing the Moon there was something very familiar about the shapes. I had seen this before. Only a few days later did it strike me: I was thinking of the “Space Window” in the National Cathedral in Washington, DC that had a small Apollo 11 Moon rock surrounded by a large circular enclosure eerily echoing our Nugget Containment Device hacked from food container lids. I had seen it dozens of times over the years. Three years later I attended the funeral of Neil Armstrong at the National Cathedral. Looking up at the window and up to the altar I found myself taping my chest where the Moon rocks were kept on my trip to Everest. I was the only one amidst this illustrious crowd who had such a resonance. One of those moments.

Space Window At The National Cathedral – The Apollo 11 Moon rock is in the center.

The Illusion of Safety

I can recall for a fleeting moment that as we hacked the Nugget Containment Device that we had just made something out of the equivalent of “bear skins and stone knives”. My oxygen deprived brain took a while to make the connection. Oh yea. That was from a Star Trek episode “City on the Edge of Forever“ where Kirk and Spock travelled back in time and Spock hacked a tricorder with old radio parts. But we had a tricorder too: a Jaz spectroradiometer kindly provided to us by Ocean Optics. We were using our tricorder to measure UV levels for an astrobiology experiment we were doing for NASA Ames.

At one point I was taking photos of Scott holding the unit against the backdrop of the Khumbu icefall which looms over Everest Base Camp. It is a dangerous obstacle that everyone climbing from the south side of Everest needs to traverse every time the climb up and down. Sherpas go up and down more than anyone else. An instant after I took a few still images of Scott with the spectroradiometer we heard a loud noise. I switched my camera to video mode and recorded one of the most violent avalanches ever recorded at Everest.

No one was hurt. But a few days later another similarly-sized avalanche killed a Sherpa guide. It almost killed Scott’s climbing partner and his Sherpa while Scott looked on with horror having just passed through the icefall only minutes before. I posted the avalanche footage on YouTube which ended up being used again and again by ESPN, Discovery Channel, and others. It was also used in the ethereal film “Sherpa“ which focused on another, but far more lethal avalanche in 2014 which killed 16 people.

Scott holding our tricorder seconds before the avalanche began

As you may recall in 2015 an immense earthquake struck Nepal. The earthquake caused a large chunk of ice and snow to roar down upon Everest Base Camp from an unexpected location opposite the Khumbu icefall. Scott and I were stunned to see that the location where so many people were killed is almost exactly where our tents were located. 19 people died that day. You can see the eventual source of the destruction directly behind this photo of us posing in front of our tents. Everest Base Camp is usually seen as a safe place – a refuge where people can rest from the risks inherent in climbing Everest.

You hear avalanches 24/7 but they never reach you at Base Camp because they never do. Everyone just assumed that being at Everest Base Camp was safe since it was always safe. But that was an illusion that people forgot to question. A safe location was not safe after all. For us two space guys this was echoes of O-rings and insulation foam – of Challenger and Columbia. Sadly my video from 2009 was suddenly popular again in 2015 – just as it was in 2014.

Keith and Scott pose for a picture in 2009 exactly where the 2015 avalanche hit

Remember

Scott left a patch on the summit that honors the crews of Apollo 1, Challenger, and Columbia. The patch designed by long-time Star Trek artist and consultant Mike Okuda and NASA JSC’s Bill Foster. Scott also wore that patch on his summit suit. Scott also took some memorial prayer flags for the crews of Soyuz 1 and 11, Apollo 1, Challenger, and Columbia.

Spaceflight memorial path on Scott’s suit and memorial banners

As you may recall that “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home“ opened with a dedication to the crew of Space Shuttle Challenger. An episode of “Star Trek Enterprise” similarly included a tribute to the crew of Space Shuttle Columbia – with Enterprise’s sister ship named “Columbia” shortly thereafter. These are but two of many references and honors to early space explorers made by Star Trek. You have only to watch the opening credits of Star Trek Enterprise to see how firmly embedded and intertwined NASA’s and Star Trek’s universes are.

Coincidently 20 May 2009 – the day Scott reached the summit of Everest – was also Flight Day 10 of STS-125 – and the crew wakeup song was the theme from Star Trek. So between Everest and outer space Star Trek got double mention on 20 May 2009. The fact that John Grunsfeld is a Star Trek fan is certainly just a coincidence.

Scott photobombing the Moon with a piece of the Moon on the Summit of Everest

In the end, a lot of our initial ideas for momentary cultural events gave way out of operational necessity to simpler things of substance – of remembrance – the prayer flags, patches, and moon rocks.

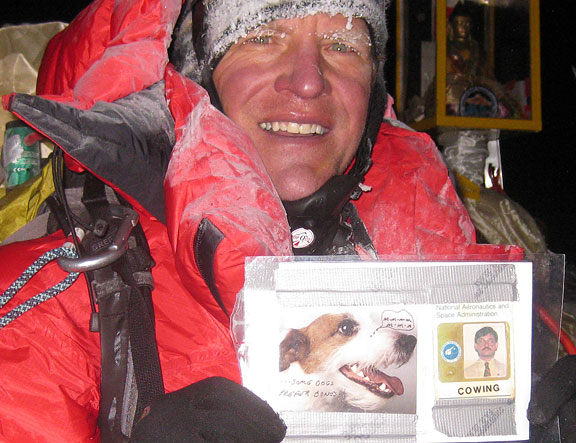

Oh yes: my old NASA badge and a picture of astronaut Suni William’s dog “Gorbie” made it there too. You’d do it too if you could.

Scott holds a picture of Suni William’s dog and my old NASA badge at the summit

That One Moment When It All Hits You

At some point on that summit morning Miles O’Brien called me and I did a live video chat with him. If you watch it you will see that I am barely visible – lit only by the computer screen and a small reading light. Many of my sentences ended a few words earlier than they should have. It was -20F at around 4 am local time. I was at 17,600 feet with minimal oxygen. I had spent the prior week sick from food poisoning. And yet there I was talking with a friend of mine in his apartment in New York City via a satellite link about our astronaut friend who was on the summit of Mt. Everest while another friend orbited overhead. Beam me up.

We departed Base Camp several days after Scott summited. Three days later we were in Kathmandu. Two days later on 28 May 2009 I arrived home after 6 weeks in Nepal. I was 21 pounds lighter, with a suntan unlike any I had ever had, feeling the after-effects of a serious case of food poisoning and utterly exhausted after 24 hours of jet travel across a dozen time zones. As with any good Star Trek story our trip to Everest was full of adventure and danger, disappointment and elation, beauty and humor, clashing cultures and profound realizations. Talk about being on an Away Team mission to an alien world.

After only 8-10 hours of sleep at home I was ready to go see the new Star Trek movie. It was the one thing I wanted to do before anything else. Then I was suddenly sitting in front of an immense IMAX screen at the National Air and Space Museum’s Udvar Hazy Facility. Most improbably Star Trek exploded outward at my face. It was so jarring it was almost like I had beamed into the battle.

At Everest my sense of reality had been irrevocably adjusted in a most improbable way by adventures and vistas that were truly of another world. How best to cement that experience into my long term memory than to now have Star Trek blast it there with phasers.

My time at Everest had a profound impact on me. Seven years later and I still think about it at least once every day. Just like a good Star Trek episode I watch it over and over again in my mind – even though I know how the episode ends. Of course, I’m also left wanting to see another episode – again, Just like Star Trek.

That’s my summary of my Star Trek episode at Everest. Keith out.

Banner image: I took this image on my way to Everest Base Camp where I lived for a month. I am not exactly sure of the peak’s name. It was outside of Lobuche. This is not me in the picture – but I had been standing in that precise spot several minutes earlier and had turned to take a picture – and my echoed self was still there. That part of me is still there. Namaste.