SpaceX Publishes Update on Starlink Satellite Brightness Issue

Yesterday SpaceX posted a comprehensive update on its Startlink satellites and the issue of light reflection that astronomers have been complaining about.

The issue hasn’t been going away and SpaceX is intent, it seems, on explaining to the astronomy community what it’s doing to mitigate the issue.

Here’s the full update from SpaceX:

Starlink Discussion – National Academy of Science

SpaceX is launching Starlink to provide high-speed, low-latency broadband connectivity across the globe, including to locations where internet has traditionally been too expensive, unreliable, or entirely unavailable. We also firmly believe in the importance of a natural night sky for all of us to enjoy, which is why we have been working with leading astronomers around the world to better understand the specifics of their observations and engineering changes we can make to reduce satellite brightness. Our goals include:

Making the satellites generally invisible to the naked eye within a week of launch. We’re doing this by changing the way the satellites fly to their operational altitude, so that they fly with the satellite knife-edge to the Sun. We are working on implementing this as soon as possible for all satellites since it is a software change.

Minimizing Starlink’s impact on astronomy by darkening satellites so they do not saturate observatory detectors. We’re accomplishing this by adding a deployable visor to the satellite to block sunlight from hitting the brightest parts of the spacecraft. The first unit is flying on the next launch, and by flight 9 in June all future Starlink satellites will have sun visors. Additionally, information about our satellites’ orbits are located on space-track.org to facilitate observation scheduling for astronomers. We are interested in feedback on ways to improve the utility and timeliness of this information.

To better explain the details of brightness mitigation efforts, we need to explain more about how the Starlink satellites work.

Starlink Orbits

Starlink has three phases of flight: (1) orbit raise, (2) parking orbit (380 km above Earth), and (3) on-station (550 km above Earth). During orbit raise the satellites use their thrusters to raise altitude over the course of a few weeks. Some of the satellites go directly to station while others pause in the parking orbit to allow the satellites to precess to a different orbital plane. Once satellites are on-station they reconfigure so the antennas face Earth and the solar array goes vertical so that it can track the Sun to maximize power generation. As a result of this maneuver, the satellites become much darker because the solar array visibility from the ground is greatly reduced.

Currently, about half of the over 400 satellites are on-station and the other half are orbit raising or in the parking orbit. Satellites spend a small fraction of their lives orbit raising or parking and spend the vast majority of their lives on-station. It’s important to note that at any given time, only about 300 satellites will be orbit raising or parking. The rest of the satellites will be in the operational orbit on-station.

Starlink Satellite

The Starlink satellite design was driven by the fact that they fly at a very low altitude compared to other communications satellites. We do this to prioritize space traffic safety and to minimize the latency of the signal between the satellite and the users who are getting internet service from it. Because of the low altitude, drag is a major factor in the design. During orbit raise, the satellites must minimize their cross-sectional area relative to the “wind,” otherwise drag will cause them to fall out of orbit. High drag is a double-edged sword–it means that flying the satellites is tricky, but it also means that any satellites that are experiencing problems will de-orbit quickly and safely burn up in the atmosphere. This reduces the amount of orbital debris or “space junk” in orbit.

This low-drag and thrusting flight configuration resembles an open book, where the solar array is laid out flat in front of the vehicle. When Starlink satellites are orbit raising, they roll to a limited extent about the velocity vector for power generation, always keeping the cross sectional area minimized while keeping the antennas facing Earth enough to stay in contact with the ground stations.

When the satellites reach their operational orbit of 550 km, drag is still a factor–so any inoperable satellite will quickly decay–but the attitude control system is able to overcome this drag with the solar array raised above the satellite in a vertical orientation that we call “shark-fin.” This is the orientation in which the satellite spends the majority of its operational life.

Satellite Visibility

Satellites are visible from the ground at sunrise or sunset. This happens because the satellites are illuminated by the Sun but people or telescopes on the ground are in the dark. These conditions only happen for a fraction of Starlink’s 90-minute orbit.

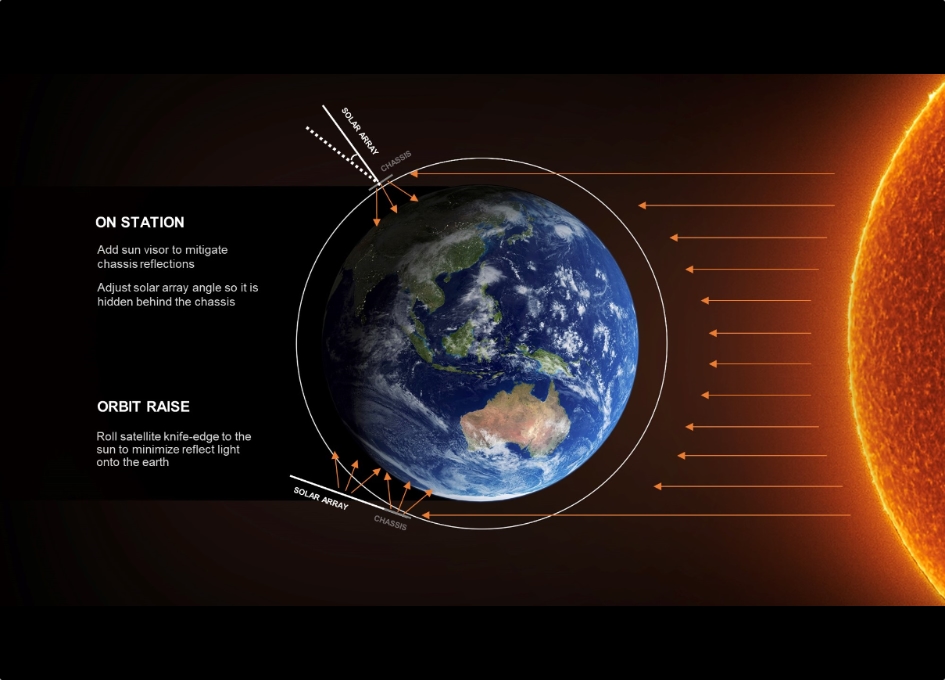

This simple diagram highlights why satellites in orbit raise are so much brighter than the satellites that are on-station. During orbit raise, when the solar array is in open book, sunlight can reflect off of both the solar array and the body of the satellite and hit the ground. Once on-station, only certain parts of the chassis can reflect light to the ground.

Physics of Satellite Brightness

The apparent magnitude of an object is a measure of the brightness of a star or object observed from Earth. It is a reverse logarithmic scale, so higher numbers correspond to dimmer objects. A star of magnitude 3 is approximately 2.5 times brighter than a star of magnitude 4. Based on observations that have been taken by us and by members of the astronomical community, current Starlink satellites have an average apparent magnitude of 5.5 when on-station and brighter during orbit raise. Objects up to about magnitude 6.5-7 are visible to the naked eye (naked-eye visibility is closer to 4 in most suburbs), and our goal is for Starlink satellites to be magnitude 7 or better for almost all phases of their mission.

There are two types of reflections off of Starlink satellites: diffuse and specular. Diffuse reflections occur when light is scattered in many different directions. Imagine shining a flashlight at a white wall. Specular reflections happen when light is reflected in a particular direction. For example, the glint of sunlight off of a mirror. Diffuse reflections are the biggest contributor to observed brightness on the ground, because diffuse reflections go in all directions. You can see diffuse reflections as long as the satellite is visible. This is why Starlink satellites can create the “string of pearls” effect in the night sky. It’s a little counter-intuitive, but the shiny components of the Starlink satellites are a much smaller problem. Whether diffuse or specular, having a high reflectance helps the satellites stay cool in space. When sunlight hits a specular surface of the spacecraft and reflects, the vast majority of light reflects in the specular (mirror reflection) direction, which is generally out toward space (not toward Earth). Occasionally when it does, the glint only lasts for a second or less. In fact, specular surfaces tend to be the dimmest part of the satellite unless you are at just the right geometry.

The biggest contributors to Starlink being bright are the white diffuse phased array antennas on the bottom of the satellite, the white diffuse parabolic antennas on the sides (not shown below), and the white diffuse back side of the solar array. These surfaces are all white to keep temperatures down so components do not overheat. The key to making Starlink darker is to prevent sunlight from illuminating these white surfaces and scattering via reflection toward observers on the ground. While in orbit raise and the parking orbit the solar array dominates due to the much larger surface area. However, once the satellites are at their operational altitude, the antennas dominate because the bright backside of the solar array is shadowed.

Solutions In-Work

We’ve taken an experimental and iterative approach to reducing the brightness of the Starlink satellites. Orbital brightness is an extremely difficult problem to tackle analytically, so we’ve been hard at work on both ground and on-orbit testing.

For example, earlier this year we launched DarkSat, which is an experimental satellite where we darkened the phased array and parabolic antennas designed to tackle on-station brightness. This reduced the brightness of the satellite by about 55%, as was verified by differential optical measurements comparing DarkSat to other nearby Starlink satellites. This is nearly enough of a brightness reduction to make the satellite invisible to the naked eye while on-station. However, black surfaces in space get hot and reflect some light (including in the IR spectrum), so we are moving forward with a sun visor solution instead. This avoids thermal issues due to black paint, and is expected to be darker than DarkSat since it will block all light from reaching the white diffuse antennas.

Early Mission (Orbit Raise and Parking Orbit) Roll Maneuver

Since the visor is intended to help with brightness while on-station, it does not shade the back of the solar array which means that it will not prevent orbit raise and parking orbit brightness. For this, we are working on changing the way the satellite flies up from insertion to parking orbit and to station.

We’re currently testing rolling the satellite so the vector of the Sun is in-plane with the satellite body, i.e. so the satellite is knife-edge to the Sun. This would reduce the light reflected onto Earth by reducing the surface area that receives light. This is possible when orbit raising and parking in the precession orbit because we don’t have to constrain the antennas to be nadir facing to provide coverage to internet users. However, there are a couple of nuanced reasons why this is tricky to implement. First, rolling the solar array away from the Sun reduces the amount of power available to the satellite. Second, because the antennas will sometimes be rolled away from the ground, contact time with the satellites will be reduced. Third, the star tracker cameras are located on the sides of the chassis (the only place they can go and have adequate field of view). Rolling knife edge to the Sun can point one star tracker directly at the Earth and the other one directly at the Sun which would cause the satellite to have degraded attitude knowledge.

There will be a small percentage of instances when the satellites cannot roll all the way to true knife edge to the Sun due to one of the aforementioned constraints. This could result in the occasional set of Starlink satellites in the orbit raise of flight that are temporarily visible for one part of an orbit.

On-Station Brightness

Satellites spend most of their lives on-station, where they will always be in the shark-fin configuration during visible passes. We can adjust the solar array positioning in this configuration to reflect light from its largely specular solar cells away from Earth, and to partially hide it behind the chassis. The main remaining goal is to block the phased arrays and antennae from direct view of the sun. The goal is to cover the white phased array antennas and the parabolic antennas on the sides of the satellite.

Using our low orbital altitude and flat satellite geometry to our advantage, we designed an RF-transparent deployable visor for the satellite that blocks the light from reaching most of the satellite body and all of the diffuse parts of the main body. This visor lays flat on the chassis during launch and deploys during satellite separation from Falcon 9. The visor prevents light from reflecting off of the diffuse antennas by blocking the light from reaching the antennas altogether. Not only does this approach avoid the thermal impacts from surface darkening the antennas, but it should also have a larger impact on brightness reduction. As previously noted, the first VisorSat prototype will launch in May and we will have these black, specular visors on all satellites by June. The parabolic antennas on the sides of the Starlink satellite also have visor-like coverings that darken them.

We have been working with leading astronomical groups in this effort–in particular the American Astronomical Society and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory–to better understand the methods and instruments employed by the astronomy community. With AAS, we have increased our understanding of the community as a whole through regular calls with a working group of astronomers where we discuss technical details, provide updates, and work on how we can protect astronomical observations moving forward. A post on some of our sessions is here. One particularly useful presentation from a member of this working group is here.

While community understanding is critical to this problem, engineering problems are difficult to solve without specifics. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory was repeatedly flagged as the most difficult case to solve, so we’ve spent the last few months working very closely with a technical team there to do just that. Among other useful thoughts and discussions, the Vera Rubin team has provided a target brightness reduction which we are using to guide our engineering efforts as we iterate on brightness solutions.

These technical and community discussions are paired with our existing efforts to make the satellites easier for astronomers to avoid. Starlink trajectories are published through Space-track.org and celestrak.com which many astronomers use in timing their observations to avoid satellite streaks. We’ve also started publishing predictive data prior to launch at the request of astronomers. These allow observatories to schedule around the satellites in the first few hours of deployment (as satellites de-tumble and enter the network).

Vera Rubin has been described as the limiting case for Starlink, due to its enormous aperture and wide field of view. These two characteristics work in concert to produce the perfect storm for satellite observations. Most astronomical systems look at an extremely small section of the sky (less than 1 degree) which makes it exceedingly unlikely that a satellite will cross in front of the imaging system in a given observation. On the other hand, systems with very large fields of view normally aren’t extremely sensitive, meaning that, while streaks will occur, they will have a small impact on the overall data collection. This is why we’ve been working so closely with the team at the Rubin Observatory. In fact, despite its wide field of view, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is sensitive enough to detect a sunlit golf ball as far away as the Moon.

So what can we do to mitigate our impact on these edge cases of wide, fast, survey telescopes?

Minimizing the Impact on Astronomy

The huge collecting area of a larger telescopes like Vera C. Rubin Observatory leads to a sensitivity that will render even the darkest satellites visible.They are so sensitive that it won’t be possible to build a satellite that will not produce streaks, in a typical long integration. There is much that can be done to reduce the impact of satellite streaks, and that starts with an understanding of how astronomical sensors work.

The astronomical community has done a great job of educating us on their imaging techniques. Optical systems use mirrors or lenses to focus light onto an imaging sensor. Most optical astronomy instruments use sensors called charge-coupled-devices (CCDs) as their detectors because astronomical targets, such as distant supernovae, and galaxies, are generally dim-at the limit of what can be detected by a sensor. For these applications, the lower noise level of CCDs’ allows for a higher signal to noise ratio for a given image, making it easier to see very faint features in the universe.

However, CCDs suffer from a key drawback, when compared to other common sensors, like the CMOS sensor in your cell phone. If you point your cell phone at a bright light, you’ll see all the pixels saturate and turn white in the region of the bright source. If you look at the same target with an optical system that uses a CCD sensor, you’ll notice that this bright spot extends to create vertical stripes on the image.

This difference is due to the way each sensor type reads the values for each pixel. While a CMOS sensor essentially has an amplifier at each pixel which turns the light collected into a digital value, a CCD sensor has a limited number of amplifiers and moves the collected light (in the form of electrons) across the sensor, to be digitized. This mechanism means that a saturated pixel on a CCD tends to wipe out data from an entire column of pixels.

This effect, commonly referred to as ‘blooming,’ is one example of how a very small but bright source of light can impact an astronomical observation. This principle is the core of our mitigation efforts. While it will not be possible to create satellites that are invisible to the most advanced optical equipment on Earth, by reducing the brightness of the satellites, we can make the existing strategies for dealing with similar issues, such as frame-stacking, dramatically more effective.

Future Satellites

SpaceX is committed to making future satellite designs as dark as possible. The next generation satellite, designed to take advantage of Starship’s unique launch capabilities, will be specifically designed to minimize brightness while also increasing the number of consumers that it can serve with high speed internet access.

While SpaceX is the first large constellation manufacturer and operator to address satellite brightness, we won’t be the last. As launch costs continue to drop, more constellations will emerge and they too will need to ensure that the optical properties of their satellites don’t create problems for observers on the ground. This is why we are working to make this problem easier for everyone to solve in the future.