Pulsar Bursts Coming From Beachball-Sized Structures

In a major breakthrough for understanding what one of them

calls “the most exotic environment in the Universe,” a team

of astronomers has discovered that powerful radio bursts

in pulsars are generated by structures as small as a beach ball.

“These are by far the smallest objects ever detected

outside our solar system,” said Tim Hankins, leader of

the research team, which studied the pulsar at the center

of the Crab Nebula, more than 6,000 light-years from Earth.

“The small size of these regions is inconsistent with all

but one proposed theory for how the radio emission is

generated,” he added.

The other members of the team are Jeff Kern, James

Weatherall and Jean Eilek. Hankins was a visiting scientist

at

Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico at the time the pulsar

observations were made. He and Eilek are professors

at the

New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology

(New Mexico Tech) in Socorro, NM. Kern is a graduate

student at NM Tech and a predoctoral fellow at the

National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Socorro.

Weatherall is an adjunct professor at NM Tech, currently

working at the Federal Aviation Administration. The

astronomers reported their discovery in the March 13 edition

of the scientific journal Nature.

Pulsars are superdense neutron stars, the remnants of

massive stars that exploded as supernovae. Pulsars emit

powerful beams of radio waves and light. As the neutron

star spins, the beam sweeps through space like the beam

of a lighthouse. When such a beam sweeps across the

Earth, astronomers see a pulse from the pulsar. The

Crab pulsar spins some 33 times every second.

British radio astronomers won a Nobel Prize for discovering

pulsars in 1967. In the years since, the method by which

pulsars produce their powerful beams of electromagnetic

radiation has remained a mystery.

With the help of engineers at the NRAO, Hankins and his team

designed and built specialized electronic equipment that

allowed them to study the pulsar’s radio pulses on extremely

small time scales. They took this equipment to the National

Science Foundation’s giant,

1,000-foot-diameter radio telescope

at Arecibo. With their equipment, they analyzed the Crab

pulsar’s superstrong “giant” pulses, breaking them down into

tiny time segments.

The researchers discovered that some of the “giant” pulses

contain subpulses that last no longer than two nanoseconds.

That means, they say, that the regions in which these subpulses

are generated can be no larger than about two feet across

— the distance that light could travel in two nanoseconds.

This fact, the researchers say, is critically important

to understanding how the powerful radio emission is

generated.

A pulsar’s magnetosphere — the region above the neutron

star’s magnetic poles where the radio waves are

generated — is “the most exotic environment in the Universe,”

said Kern. In this environment, matter exists as a plasma,

in which electrically charged particles are free to respond

to the very strong electric and magnetic fields in the

star’s atmosphere.

The very short subpulses the researchers detected

could only be generated, they say, by a strange process in

which density waves in the plasma interact with their

own electrical field, becoming progressively denser

until they reach a point at which they “collapse explosively”

into superstrong bursts of radio waves.

“None of the other proposed mechanisms can produce such

short pulses,” Eilek said. “The ability to examine these

pulses on such short time scales has given us a new

window through which to study pulsar radio emission,”

she added.

The Crab pulsar is one of only three pulsars known to

emit superstrong “giant” pulses. “Giant” pulses occur

occasionally among the steady but much weaker “normal”

pulses coming from the neutron star.

Some of the brief subpulses within the Crab’s “giant” pulses

are second only to the Sun in their radio brightness in

the sky. Although the mechanism that converts the plasma

energy to radio waves in the Crab’s “giant” pulses may be

unique to the Crab pulsar, it is feasible that all radio

pulsars may operate the same way. The research team now

is observing signals from other pulsars to see if they

are fundamentally different. The subpulses in the Crab’s

“giant” pulses are so strong that the team’s equipment could

detect them even if they originated not in our own Milky

Way Galaxy, but in a nearby galaxy.

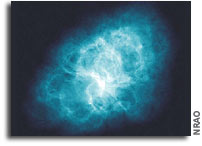

The Crab Nebula is a cloud of glowing debris from a star

that was seen to explode on July 4, 1054. Chinese

astronomers noted the bright new star that outshone the

planet Venus and was visible in daylight for 23 days. A

rock carving at

New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon probably

indicates that Native American skywatchers also noted

the bright intruder in the sky.

The nebula was discovered by John Bevis in 1731 and

independently rediscovered by French astronomer Charles

Messier on August 28, 1758. Messier made the Crab

Nebula (named because of its crab-like shape) the first

object in his famous catalog of non-stellar objects, a

catalog widely popular among amateur astronomers with

small telescopes.

In 1948, radio emission was discovered coming from

the Crab Nebula. In 1968, astronomers at Arecibo Observatory

discovered the pulsar in the heart of the nebula. The

following year, astronomers at Arizona’s Steward Observatory

discovered visible-light pulses also coming from the pulsar,

making this the first pulsar found to emit visible light

in addition to radio waves.

The

National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the

National Science Foundation, operated

under cooperative agreement by

Associated Universities, Inc. The

Arecibo Observatory is

part of the National Astronomy and

Ionosphere Center, which is operated by

Cornell University

under a cooperative agreement with the

National Science Foundation..

Contacts:

Dave Finley, National Radio Astronomy Observatory

Socorro, NM

(505) 835-7302

dfinley@nrao.edu

George Zamora, New Mexico Tech

(505) 835-5617

gzamora@nmt.edu

David Brand, Cornell University

(607) 255-3651

deb27@cornell.edu