“Not Culture but Perhaps a Cult”, Op Ed on NASA and the Shuttle by Homer Hickam

At the end of the movie “October Sky” which was based on my memoir Rocket Boys, there is a dramatic launch of the Space Shuttle. The director of the film wanted to show the transition from my small amateur rockets in West Virginia to the huge professional rockets of NASA as a metaphor for my own transition from coal-town boy to big-time space engineer. The scene works wonderfully. When I was at the Venice Film Festival, the audience rose to their feet after this scene and applauded me while tears streamed down their faces. When I go to the Cape and watch the Shuttle being launched, I still get a lump in my throat watching it soar aloft. Even though I no longer work for NASA, its thunder affirms my dreams for spaceflight. Still, when I put emotion aside, I cannot ignore my engineering training. That training and my knowledge as a twenty-year veteran of the space agency (and also a Vietnam veteran) has led me to conclude that the Space Shuttle Program may well be NASA’s Vietnam. A generation of engineers and managers have exhausted themselves trying to make it work and they just can’t. But why not? I believe it is because the Shuttle’s engineering design, just as Vietnam’s political design, is inherently flawed.

Much has been made over the report produced by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB). I have since read newspaper articles that called the report “scathing.” Hardly. Its polite recommendations probably had Shuttle managers who made poor decisions dancing down their office hallways with relief. Essentially, it gave them a pass by proclaiming “culture” made them do it. It is an echo of the Rand Commission’s study on the Shuttle Program produced almost exactly one year ago which also wrung its hands over the NASA culture, though with a different conclusion (turn the whole thing over to contractors).

I do not believe there is a NASA culture other than a willingness by its engineers to work their butts off to keep us in space. It might be said, however, that there is a Shuttle cult. It is practiced like a religion by space policy makers who simply cannot imagine an American space agency without the Shuttle. Well, I can and it is a space agency which can actually fly people and cargoes into orbit without everybody involved being terrified of imminent death and destruction every time the Shuttle lifts off the pad.

With some important reservations, the CAIB recommended to keep the Shuttles flying but with more inspections, more bureaucracy (an outside safety agency to keep an eye on everybody involved), and more money. But I think piling on more inspections and people and dollars won’t make the Shuttle any safer. Neither will the safety sensitivity training that will be probably be dumped on top of already overworked and disillusioned NASA engineers. My God, they’ve already dedicated their lives, their very souls, to keep the Shuttle flying safely! The truth is no amount of arm-waving and worrying about “culture” can fix a flawed design. Every engineer knows a design that tries to bypass the realities of physics, chemistry, and strengths of materials by applying complexity will fail eventually no matter how much attention is given to it.

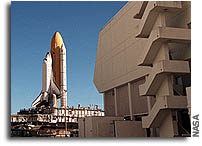

Take a look at the Shuttle stack and what do you see? A fragile spaceplane sitting on the back of a huge propellant tank between two massive solid rocket boosters. The tank holds liquid oxygen and hydrogen and towers above the spaceplane. It is the foam off this tank that hit Columbia and knocked a hole in her wing. But why is there foam at all? Because without it, ice would form on the super-cooled tank and hit the spaceplane. But why would ice or foam hit it in the first place? Because of where the spaceplane sits. But why does it sit there? Because the Shuttle Main Engines (SME’s) need to come back to Earth and therefore must be attached to the spaceplane to be returned. And why do the SME’s need to be returned? So that they can be reused. And why do they have to be reused? Because, theoretically, it’s cheaper to refurbish them than build new ones. Therefore, the spaceplane we think of as the Shuttle has to sit right in the middle of all the turmoil of launch because we once believed it would be cheaper to bring back those engines and rebuild them than to build new ones. That has not proved to be the case-far from it-but it has left us with a crew sitting in the most vulnerable position possible in terms of engineering design and safety. Simply put, had that spaceplane been on top of the stack, the destruction of Columbia would not have occurred because its wings would have been out of the line of fire. Challenger would probably not have happened, either. Had the spaceplane been above the explosion, it likely would have been able to punch out and glide back home.

The flawed design of the Shuttle is all in its history and it’s more than the way the stack is assembled. For instance, the Shuttle uses hydrogen fuel, the most difficult, cranky fuel there is. Hydrogen is the smallest atom in the universe and leaks through molecule-sized pinholes. When it gathers in an enclosed space (such as under the shuttle stack on the pad), it’s a bomb waiting to go off. Hydrogen leakages grounded the Shuttles for three months before Columbia was launched and scares a lot of NASA engineers to death. So why do they use hydrogen and all its cranky plumbing? Because the Shuttle’s original designers had to wring the last ounce of performance out of it to haul those mains into orbit along with the heavy payloads that the Air Force demanded at the time (the Air Force long ago gave up on the Shuttle). And what about those solid rocket boosters, unstoppable once lit? They leave the crews with no choice but to hang on until they’ve wound down even if their spaceplane is being torn apart. They were added not because they were the best boosters around but because they were relatively cheap. If his engineers had brought my father something to dig coal as flawed in its suppositions as well as its design as the Shuttle, he would have chased them out of his coal mine.

The odd thing is that the Shuttle was designed by great engineers. The problem is they were forced to fit their designs to fit what has proved to be an impossible concept, a chemically-propelled rocket ship that would carry humans and heavy payloads into orbit routinely, then land to be refurbished and sent aloft again within days. They also had to do it on the cheap. It was inevitable that a flawed design would be the result. In my second memoir The Coalwood Way, I wrote about me always complaining about the past until Roy Lee, a fellow Rocket Boy, tells me to stop it because “You can’t beat history.” And he was right even though, as I wrote, “It placed my heart in the icy vise of truth where hearts tend to suffer.” The heart of every NASA engineer suffers today in this icy truth: the Space Shuttle is an inherently flawed design and will destroy American human spaceflight if we don’t get it behind us. It’s nearly done it already.

So what should be done? Let’s get practical. We can’t just shut the thing down instantly. History’s got us by the throat. We need the Shuttle to finish the space station and to also keep the Russians and Chinese from dominating space. I for one am not willing to see that occur while we dither. Human spaceflight is important to this country. But I think the Shuttle is as safe as you’re going to get it pretty much with what is in place today. Let’s fire the managers responsible for Columbia (they are not difficult to identify) so as to warn the next crop they’d best be competent, put the toughest engineers we can find to be in charge of the program, fly the thing eight to ten more times over the next four years to finish the space station and meet our international obligations. Then let’s close the program down in a controlled fashion and replace it with proven expendable launchers and a shiny new spaceplane. And, this time, put it on top.

Homer Hickam’s new novel, The Keeper’s Son, will be released by St. Martin’s in September, 2003. See www.homerhickam.com.

Editor’s note: A shorter version of this editorial appeared in the Wall Street Journal.