Do Budget Cuts Mean an End to Flagship Programs?

The following article is a free sample from the current issue of Space Quarterly Magazine. It is our hope that if you enjoy this article you will consider subscribing to the magazine.

—

Do Budget Cuts Mean an End to Flagship Programs?

by Marcia S. Smith

The Obama Administration’s decision to cut NASA’s planetary exploration budget for FY2013 and beyond generated howls of protest. The action forced the United States to shelve planned cooperation with the European Space Agency (ESA) on two Mars probes in 2016 and 2018 that were the beginning of a string of missions to fulfill the holy grail of Mars scientists – returning a sample of Mars to Earth for analysis.

As the weeks have passed, however, the news turns out to be not nearly as dire as first imagined. While the future of Mars cooperation with ESA remains unclear, a smaller U.S. mission in 2016 is a possibility and NASA is working to define a mid-sized mission that it hopes to launch in 2018 or 2020. Simultaneously, the agency is reformulating its overall Mars exploration strategy to create an integrated approach that responds to the needs of both the science and the human exploration goals of the agency.

With Congress preparing to restore $100-150 million of the money the President proposed to cut in FY2013, one almost has to ask what the fuss is all about. The series of missions leading to a Mars sample return in the next decade recommended by the National Research Council (NRC) in last year’s planetary science Decadal Survey and NASA’s reputation as a partner in international science projects remain at risk, but even those may survive.

The Budget Cut Heard ‘Round the World

The Obama Administration’s fiscal year (FY) 2013 budget request for NASA is $17.71 billion, a slight decrease from the $17.77 billion it received for FY2012. Of that, the request for the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) is $4.91 billion, a little less than the $5.07 billion it got for FY2012. With determination to cut the federal deficit driving everything in Washington, austerity is the watchword amid widespread sentiment that NASA did not fare badly at all.

The ruckus is because the cut to the SMD was directed at planetary science rather than spread over all the SMD disciplines, including astrophysics, heliophysics and earth science. The request for planetary science is $1.2 billion, a 21 percent cut from the $1.5 billion it got for FY2012, while the other areas get increases. Aggravating planetary scientists in particular is the increased spending on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) with its severe cost overruns. An often heard complaint is that the money from planetary science was used to pay for those overruns though NASA officials decline to make that connection.

NASA and White House officials insist that they have nothing against planetary exploration generally or Mars specifically. Instead, the reasons for cutting that part of NASA’s science program were two-fold, they say. First, with a rover (Opportunity) and two U.S. orbiters (Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) already investigating Mars, another rover (Mars Science Laboratory/Curiosity) on the way, and another orbiter (MAVEN) scheduled for launch next year, Mars exploration is doing fine. Second, the United States is not in a financial position to commit to the long term series of expensive “flagship” missions planned for Mars sample return, of which the 2016 and 2018 missions with ESA were the first. The 2016 ESA-led ExoMars mission is an orbiter that was to include a demonstrator to

test entry-descent-and-landing (EDL), while the 2018 NASA-led mission was to be a rover.

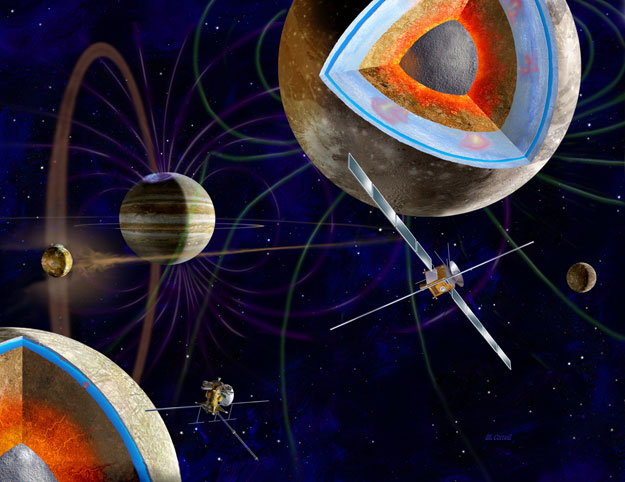

Artist’s impression of the Europa Jupiter System Mission which the European Space Agency might undertake with Russia and Japan after NASA funding became in doubt. NASA/ESA/Artist Michael Carroll

Flagships or No Flagships?

During a briefing to the NASA Advisory Council’s Science Committee March 6, SMD chief John Grunsfeld said that the Obama Administration did not want to approve any more flagship missions until NASA had completed its current flagships, JWST and the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) and its rover, Curiosity. MSL also overran its budget and suffered a two-year launch delay because of technical problems.

Grunsfeld’s comment prompted speculation about whether an anti-flagship sentiment was resurfacing. In the 1990s, overruns, delays and failures on large science missions led to their being derisively referred to as “Battlestar Gallaticas” after a sci-fi television show of that era. Then-NASA Administrator Dan Goldin instituted a “faster, better, cheaper” philosophy of launching smaller missions more frequently instead of large, complex flagship missions.

With the passage of time, however, it became apparent that some scientific questions could not be answered with the smaller missions and flagships returned. For Mars, it was MSL, which launched in 2011, two years late and well over budget. It will land on Mars on August 6 EDT (August 5 PDT) using a technically challenging “sky crane” design that will have mission managers holding their breath until a signal is received that it is safely on the surface.

Despite the problems with JWST and MSL, however, Paul Shawcross, Branch Chief for Science and Space at the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB), denies that the White House opposes flagships. He told the National Research Council’s (NRC’s) Space Studies Board on April 4 that “we’re not against flagships” and there was no “bias against Mars.” He insisted that the decision to cut Mars funding was budget-based.

Indeed, the “bible” of the planetary science community, the NRC’s 2011 planetary science Decadal Survey, gave just that advice to NASA – if money becomes tight, cut flagships first.

The NRC, part of the National Academies, conducts Decadal Surveys at NASA’s request for each of NASA’s science disciplines every 10 years (hence the name “decadal”). These highly respected documents usually are faithfully followed by NASA and Congress because they represent a hard-won consensus of the scientists most directly involved in a scientific discipline, whether planetary science, astrophysics, heliophysics or earth science. The studies prioritize the most important scientific questions and identify missions to answer them.

The 2011 planetary science Decadal Survey, for the first time, not only identified priorities, but provided decision rules to guide NASA in the event budgets were less than expected. The study was chaired by Cornell University’s Steve Squyres, best known as the “father” of the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity. At a February meeting of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG), he stressed that the overarching consensus of the planetary science community was to protect the smaller missions in the Discovery and New Frontiers programs, along with Research and Analysis (R&A) and technology development. If anything had to be cut, the Decadal Survey’s advice was to go after flagships first, exactly the path the Obama Administration followed.

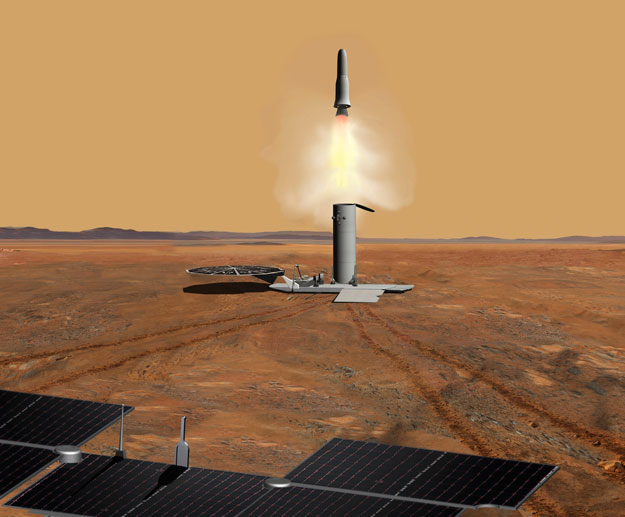

This artist’s concept of a proposed Mars sample return mission portrays the launch of an ascent vehicle. The solar panels in the foreground are part of a rover. The rover would have delivered to the ascent vehicle a cache of Martian rock samples that would have been left on the surface by a previous sample-collection rover. The ascent vehicle would release its sample container in Martian orbit, to be retrieved by a spacecraft for carrying the samples to Earth. NASA/JPL Caltech

A New Plan for Mars Exploration

Although the Administration decided against the Mars flagship missions planned with ESA for 2016 and 2018, at his February 13 budget briefing, Grunsfeld announced that he was initiating an effort to define a more affordable mission for launch in 2018. Mars and Earth are properly aligned in their orbits around the Sun every 26 months and some of those alignments are better than others. Grunsfeld calls 2018 a “sweet spot” and does not want to waste it. He concedes, however, that budgets may mean the mission will have to wait until the next opportunity in 2020.

He is not ruling out a mission in 2016 either. One of three missions competing in the Discovery category of smaller missions for launch in 2016 is a Mars mission called Geophysical Monitoring Station (GEMS). With MAVEN getting ready for launch in 2013, it may turn out that NASA does not miss any of the planetary alignment opportunities. NASA has launched probes to Mars at every opportunity since 1996 with one exception – 2009 – and only then because MSL was not ready.

Grunsfeld created the Mars Program Planning Group (MPPG) to define options for an affordable mission for 2018. MPPG is led by former NASA Mars Exploration Program Director Orlando Figueroa and is due to make its recommendations in August. The figure of $700 million has been mentioned as a target cost for the mission. At an April 13 teleconference updating MPPG’s progress, Doug McCuistion, current Mars Exploration Program Director, revealed that the money for this new Mars mission is already in his budget. Granted, budget projections beyond the current year are just that, projections, not promises, but it is a strong indication that the Obama Administration supports the idea.

One question is whether that $700 million is best spent on a Mars mission that was not identified as a priority in the Decadal Survey, but is only now being conceptualized. The whole point of the Decadal Survey is to look at all the scientific priorities for solar system exploration – not only Mars – and decide what should be done first. Squyres said at the MEPAG meeting that under the Decadal Survey’s decision rules, new missions to Mars “that lead directly to sample return” have very high priority, but any mission that does not should be openly competed in the Discovery program, not given an automatic nod. Thus, if whatever emerges from the MPPG does not “lead directly to sample return,” it would be inconsistent with the Decadal Survey, even though the money apparently already has been put in the Mars budget line.

Congress is very supportive of Mars exploration – and of Decadal Survey recommendations. On April 19, the House Appropriations Commerce-Justice-Science (CJS) subcommittee approved its version of the bill that will fund NASA for FY2013, adding $150 million for planetary exploration. It stipulates that the money be used for a Mars mission, but only if the NRC certifies that it is consistent with the Decadal Survey. If not, the money will go to the Decadal Survey’s second priority for flagship missions, a probe to study Jupiter’s moon Europa. The same day, the Senate Appropriations Committee approved its version of the bill, adding $100 million for a Mars mission, without the conditions included by the House subcommittee.

Meanwhile, Grunsfeld, a former astronaut as well as a scientist, is leading a makeover of NASA’s overall Mars exploration strategy. NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden tapped Grunsfeld to lead an intra-agency NASA team to reformulate the agency’s strategy for exploring Mars. The new plan is intended to address the needs of both SMD and the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate (HEOMD). Grunsfeld, HEOMD Associate Administrator Bill Gerstenmaier, Chief Scientist Waleed Abdalati and Chief Technologist Mason Peck are devising an “integrated strategy” of robotic and human space exploration to meet President Obama’s mandate to send people to the vicinity of Mars in the 2030s.

The proposed Flagship mission Titan Saturn System Mission would consist of a NASA orbiter and an ESA lander and research balloon. NASA/ESA

International Cooperation

What does all this mean for international cooperation? NASA has a rich history of international cooperation dating back to its origin in 1958. The poster child is the 15-nation International Space Station (ISS) that brings together the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan and 11 European countries acting through ESA.

ESA is NASA’s closest international partner, particularly in space science. In 2009, NASA and ESA signed an agreement to essentially merge their Mars exploration programs. As Obama Administration officials carefully point out, the agreement did not commit either side to participate in any joint missions. Rather it was a framework for ESA and NASA to work together to define “the most viable joint mission architectures.” Still, the intent was clear – not simply choosing a single mission on which the two agencies would cooperate as done so many times in the past, but a new approach, joint planning for a series of missions over many years leading to a sample return from Mars.

NASA informally signaled ESA last summer that budget constraints might require a change in plans, but formal notification had to await release of the FY2013 budget in February. ESA had discussions with Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, last year to determine its level of interest in joining ExoMars. ESA and Russia also have a history of cooperation. Russia lost its Mars probe, Phobos-Grunt, in a November 2011 mishap, and was open to the possibility. It now has replaced the United States as ESA’s partner on ExoMars.

NASA officials insist that international cooperation is essential to its programs and certainly wants to continue working with ESA. Jim Green, Director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, publicly praises ESA for responding “with vision and not with anger” at NASA pulling out of ExoMars. ESA’s Rolf deGroot, who heads the ExoMars program, was gracious at the February MEPAG meeting. When asked if ESA might be interested in participating in whatever program emerges from the MPPG deliberations, de Groot said “We are open to discuss any opportunities for cooperation.”

NASA’s international partners are accustomed to the zigs and zags of the U.S. space program, not that it makes such changes any easier to digest. One may wonder why any country chooses to cooperate with us at all. The answer probably lays in the fact even at a reduced level of $1.2 billion, the NASA planetary science budget dwarfs that of any other space agency and NASA’s technical prowess is unmatched.

So despite the need for extreme flexibility when cooperating with the United States, many countries do and the majority of NASA’s science missions involve international cooperation. Grunsfeld estimated at the April 13 MPPG update that three quarters of NASA’s science missions are international. As for the international ramifications of walking away from the 2016 and 2018 Mars missions, OMB’s Joydip (JD) Kundu told the NRC Space Studies Board on April 3 that budget constraints demanded that something in SMD be cut, and whatever mission was chosen probably would have involved reneging on an international commitment.

What’s Next?

The MPPG report is due in August, the same month that MSL’s rover, Curiosity, will land on Mars. Whether that landing succeeds or fails could be a factor in support for future Mars probes. As noted, the $2.5 billion mission is relying on a technically challenging system called a sky crane that looks precarious in a YouTube video animation.

Though public fascination with Mars seems to transcend failures like the three that occurred in the 1990s (Mars Observer, Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander), prognosticating on what will happen if Curiosity fails is itself a risky business. In today’s environment with every penny being counted, enthusiasm for the increases currently included in the House subcommittee and Senate committee versions of NASA’s funding bill could evaporate. A successful landing, conversely, could fuel subsequent Mars budget increases.

Mars is not the only fascinating object in the solar system and scientists advocating missions to the outer planets are vying for the same pot of money. Whatever happens with Mars this year, the budget wars are far from over.