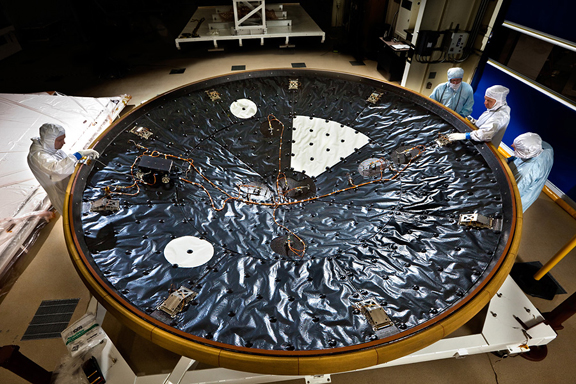

Mars Science Laboratory Entry, Descent and Landing Instrumentation (MEDLI)

The MSL Entry, Descent and Landing Instrument (the black box in the middle left of the photo) is scheduled to launch as part of the Mars Science Laboratory mission November 25. MEDLI will measure heat shield temperatures and atmospheric pressures during the spacecraft’s high-speed, extremely hot entry into the Martian atmosphere. Credit: Lockheed Martin

NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory is expected to improve not only our knowledge of Mars but also the science of hypersonic flight — more than five times the speed of sound — within an out-of-this-world atmosphere. That’s something of great interest to NASA researchers who study flight through all atmospheres so they can help design better air and spacecraft.

The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Curiosity rover is protected by an encapsulating aeroshell made up of a heat shield and back shell. Embedded in the MSL heat shield is a set of sensors designed to record the heat and atmospheric pressure experienced during the spacecraft’s high-speed, extremely hot entry into the Martian atmosphere. The sensor suite is called MEDLI, which stands for MSL Entry, Descent and Landing Instrumentation.

“This is the first time we’ve ever had sensors that will collect accurate, high fidelity data of atmospheric entry at another planet,” said Jim Pittman, head of the Hypersonics Project, which is part of the Fundamental Aeronautics Program in NASA’s Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate (ARMD). “Having that knowledge is of great interest to the hypersonics community — especially when it comes to being able to design future Mars entry systems that are safer, more reliable and lighter weight.”

NASA’s ARMD is one of the sponsors of the $28 million MEDLI system research, development and data analysis. It also has support from NASA’s Science and Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorates, and is the first Technology Demonstration Mission from NASA’s Space Technology Program to go into space.

One set, MEADS (Mars Entry Atmospheric Data System), required that seven one tenth-inch diameter holes be drilled into the heat shield in a special cross pattern. Those holes are ports for pressure sensors that will measure the atmospheric pressure on the heat shield at the seven MEADS locations during entry and descent through Mars’ atmosphere.

“This isn’t the first time we have drilled tiny holes in a spacecraft,” said Neil Cheatwood, MEDLI principal investigator. “In the 80s we installed pressure sensors in the nose cap of the space shuttle to study hypersonic flow. We have done extensive testing to make sure the MEADS pressure ports can withstand the heat of entry.”

The sensors’ cross pattern will allow engineers to determine the orientation of the MSL aeroshell and how it changes with time over the less than 10 minutes it takes to go from the top of the atmosphere to the surface. Engineers will use this information to see how well their computer models predicted the spacecraft’s path and aerodynamics, as well as determining the atmospheric density and winds it encountered.

The other set of seven sensors, MEDLI Integrated Sensor Plugs or MISP, will measure how hot it gets at different depths in the spacecraft’s heat shield material. Predicted heating levels are about three times higher than those of the space shuttle when it entered Earth’s atmosphere. The heating levels are so high, in fact, that the spacecraft’s thermal protection system is designed to burn away during entry into Mars’ atmosphere. MISP will measure the rate of this burning, so researchers can compare real data to their predictions.

MEDLI will collect its data in the last eight minutes of the Mars Science Laboratory’s flight next August. That’s about how long it takes to slow the spacecraft from 13,000 to just under two miles an hour. Instruments will record the heat and atmospheric pressure experienced during entry and descent, then turn off before ejection of the heat shield and landing.

The data will be stored on the Curiosity rover, then sent back to Earth so that aeronautics researchers can study it and gain a better understanding of spacecraft performance during hypersonic flight into a planetary atmosphere.