The Near Term Future of On-Orbit Servicing is Robotic

Currently, over “$500 billion dollars in satellite assets are stationed in geosynchronous orbit (GEO),” according to Gordon Roesler, a program manager in the Tactical Technology Office at the Defense Advanced Projects Research Agency (DARPA), and if those assets break down, “given the remote, heavily radiated atmosphere of GEO, a company only has one replacement option at this time – launching a replacement system.”

Launching replacement systems is an expensive undertaking for companies, as is system failure, because “insurance on satellite systems only covers the cost of the system, not the disrupted business,” explained Maj. Gen. Jim Armor, Jr., U.S. Air Force (retired) and vice president of strategy and business development for ATK’s Space Systems Division explained to the audience attending the “The Near-Term Future of On-Orbit Servicing” panel at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) SPACE 2014 Forum in San Diego, last week. Armor further clarified that there will be “nearly 200 satellite systems reaching retirement by 2020,” forcing lots of replacement decisions.

Discussing the future of on-orbit servicing, two panelists profiled their companies’ efforts to develop robotic solutions for solving satellite problems in GEO.

Roesler profiled DARPA’s Phoenix project, which should come on-line by 2019. According to Roesler, Phoenix will offer users a “fifteen year life span and electric propulsion systems,” as well as a variety of services, including: “autonomous docking capability with the damaged satellite, the ability to change the satellite’s attitude and altitude, as well as robotic arms and tool suites to affect the repairs.”

Roesler also noted that Phoenix will offer “high resolution imaging capability that will allow for better diagnosis of the damage to the satellite system,” which Roesler called “CSI in space,” and in which “insurance companies are extremely interested.”

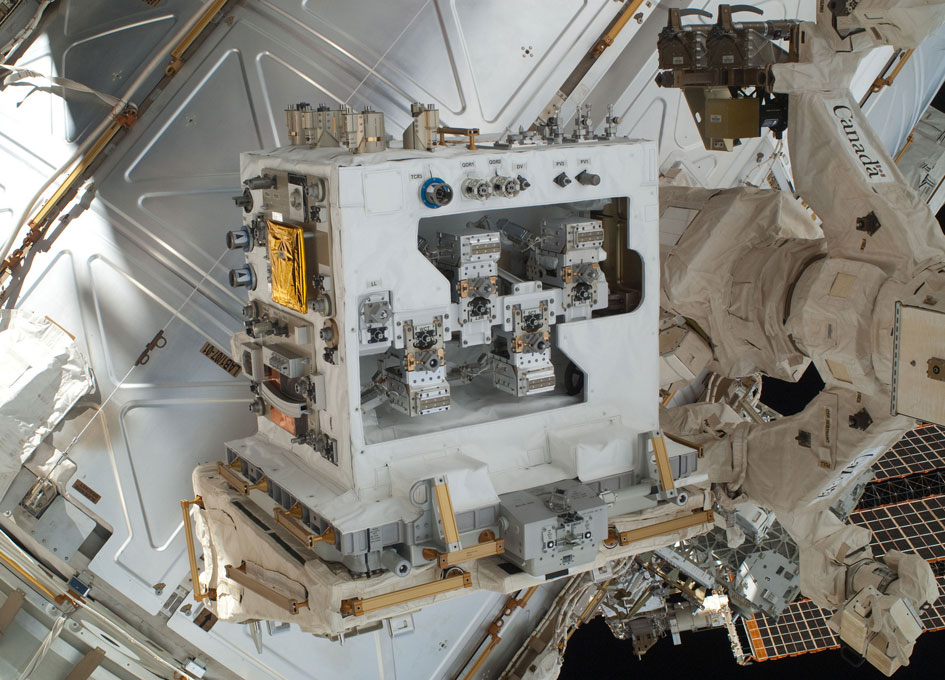

Armor briefed the audience on ATK’s Mission Extension Vehicle (MET) project, produced by ATK’s ViviSat program in partnership with U.S. Space. Armor explained that the initial iterations of MET would be able to “dock with satellites and provide attitude adjustment assistance and propulsion power with no mission disruption.” The MET units will use “electric propulsion, have a life span of “16 years,” and a “lift capacity above 200 kilograms,” giving MET a “huge amount of hosted payload and rideshare capabilities.” Later versions of MET will include “robotic arms capable of doing minor maintenance work.” The long-term goal for MET, according to Armor, “would be a refueling mission.”

Despite ongoing efforts to deploy robotic servicing, some barriers remain to expanded progress. Dr. David Akin, an associate professor and director of the Space Systems Laboratory in the Department of Aerospace Engineering, at the University of Maryland College Park, identified three.

First, he urged abandonment of “the attitude that robotic development is rocket science squared,” continuing “yes, it’s hard, everything we do as hard, but we have to remember that not so hard that only the anointed few who have done it can ever do it,” urging more companies to jump into the field. Second, he asked that companies remember that not every “genius works at NASA,” noting that there are plenty of great ideas about space robotics in academia and corporations that can be tapped. He ended by noting “the U.S. is not the world leader in robotics, and we only have a limited time to lead in-space robotics,” to avoid not seizing that lead, Akin urged companies to abandon what he termed the “Highlander syndrome,” the myopic thinking that they must build “one robot that can do everything,” which discourages firms from entering the market if they feel their robot can’t do everything.

Dan King, vice president of business development at MDA, closed the panel by stating that successful and consistent orbital servicing by robotic systems will “require a considerable effort between government and private industry, but that this is doable and we can manage the risks well.”

By Duane Hyland